In Bajirao Mastani, love does not whisper; it thunders. It rides in on a horse, drenched in rain, sword flashing, eyes ablaze. It prays as it wounds, and it bleeds as it worships.

Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s film — drenched in scarlet and gold, sung like an epic poem — is not simply a love story. It is a theological crisis. It asks what happens when passion dares to question divine order, when devotion begins to resemble blasphemy.

This is not a romance between man and woman. It’s a collision between soul and duty, between the sacred and the forbidden.

Love as Heresy

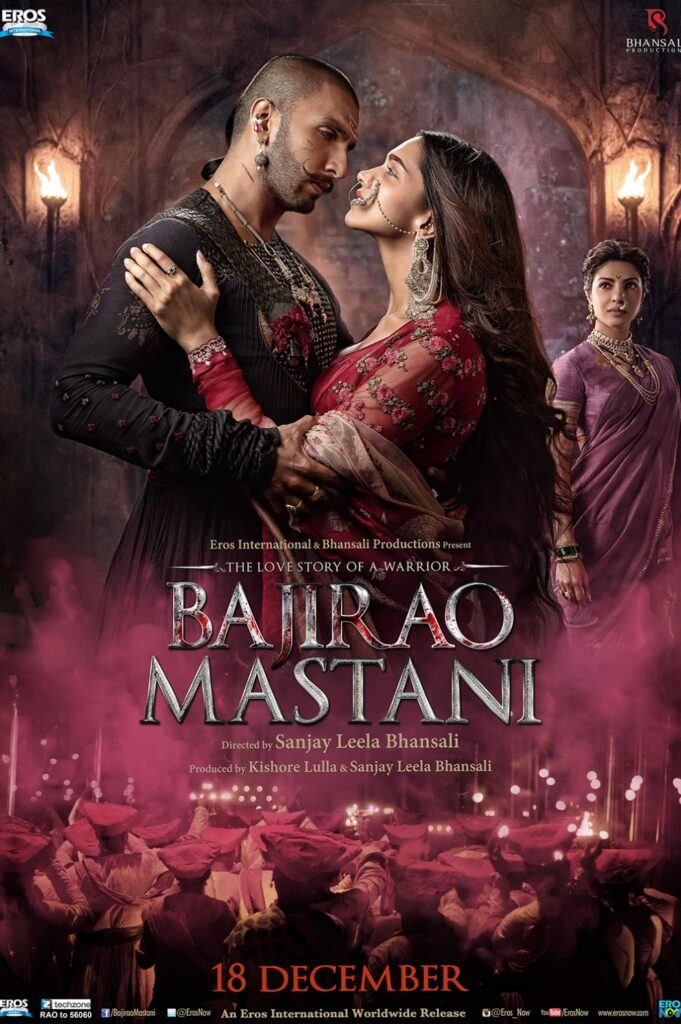

When Mastani (Deepika Padukone) first enters Bajirao’s (Ranveer Singh’s) life, she doesn’t ask to be loved — she demands it, like destiny arriving on horseback. She is Muslim, he is Hindu; she comes to seek protection, but what she really seeks is recognition.

In the moral geometry of Bajirao’s world, love must obey the lines drawn by caste, religion, and propriety. Mastani’s love, therefore, is a scandal. But Bhansali’s lens turns that scandal into sanctity. Her love isn’t transgression — it’s truth.

When she says, “Aap mere khuda ho” — you are my god — it is not submission; it’s declaration. In a society that demands women love quietly, Mastani loves with scripture-breaking audacity.

Love here is rebellion written in verse.

Faith as Battlefield

Bhansali renders faith not as comfort but as conflict. The temples and palaces of Bajirao Mastani gleam like sanctuaries, but they’re haunted by ideology. The priests, the courtiers, the family — all wield religion as weapon.

The film’s great tragedy is that Bajirao’s war against enemies abroad is simpler than his war at home. He can conquer kingdoms, but not prejudice.

Faith becomes the true antagonist — not Islam or Hinduism, but faith as hierarchy, faith as possession. When the Brahmins denounce Mastani, when Kashibai (Priyanka Chopra) watches her marriage decay in silent dignity, the film trembles with an unbearable awareness: holiness can be cruel, and love can be divine.

The Feminine Divine

Bhansali’s women are never weak — they are elemental. Kashibai is grace and heartbreak incarnate, a woman who smiles as the world collapses around her. Mastani is flame and faith intertwined — saint and sinner in one luminous body.

Both are bound by the same structure that exalts their virtue and denies their agency. Yet each resists in her own way: Kashibai through restraint, Mastani through radiance. Their suffering is not passive — it is the slow, deliberate endurance of those who have learned that silence can also be weapon.

The women of Bajirao Mastani are temples that refuse to crumble.

The Empire of the Soul

The film’s true empire is not land — it’s emotion. Every corridor, every courtyard, every monsoon seems to exist to echo Bajirao’s turmoil. Bhansali builds architecture out of feeling: the towering chandeliers, the flickering lamps, the veils of smoke. This is not historical realism; it’s psychological grandeur.

The cinematography turns the inner world outward — love is color, sorrow is light. Gold glows when Mastani smiles; blue floods the frame when Kashibai weeps. Fire dances, water mourns, and marble listens.

Every gesture is devotional, every tear an offering.

Honor and Desire

Bajirao’s tragedy is that he confuses conquest with control. A general who has never known defeat in battle meets a woman who teaches him the art of surrender. In his love for Mastani, he finds a kind of faith that terrifies him — faith without boundaries.

His world cannot forgive him for it. The Maratha court sees his heart as betrayal, his passion as pollution. Bhansali stages this not as melodrama, but as ritual — a society purging what it cannot understand.

In the end, Bajirao’s delirium — his vision of Mastani riding toward him in light — becomes prophecy. Love survives him. Love, as always in Bhansali’s world, refuses to die neatly.

The Aesthetics of Devotion

Bajirao Mastani is a film painted in prayer. Every song is a psalm, every frame a temple mural. The camera moves like incense — slow, reverent, circling its subjects as though afraid to disturb them.

Bhansali’s excess is never wasteful; it’s worshipful. His opulence is his theology: to love beautifully is to believe.

In one extraordinary moment, Mastani dances in the Diwan-e-Khas, surrounded by soldiers who see her as impurity. Her dance is luminous defiance — the body turned into revolution. She does not argue; she performs her truth. And truth, once performed, cannot be unseen.

Love Beyond Death

As the film spirals toward its end, time itself seems to dissolve. Bajirao’s victories mean nothing; his titles are ashes. What remains is faith — not in gods, but in connection.

When he collapses, fevered and hallucinating, seeing Mastani’s spirit galloping toward him, it’s as if Bhansali is rewriting the laws of separation. The lovers’ union defies mortality; death becomes only another form of devotion.

The film closes like a prayer — two souls dissolving into legend, the world still arguing about their sin while their spirits have already found peace.

Conclusion: The Temple of Fire and Rain

Bajirao Mastani is a love story set against the tyranny of order — an epic about how societies fear the intensity of feeling they cannot regulate. It’s about how faith can sanctify love or destroy it, how devotion can burn as brightly as it heals.

For Bhansali, history is just pretext; what he’s really filming is transcendence.

And so, the film leaves us with this final paradox: love is both weapon and wound, rebellion and surrender. The rain falls, the lamps flicker, the drums echo. The lovers vanish into myth — but the light stays behind, trembling like a memory that refuses to fade.

Because in Bajirao Mastani, love does not end.

It becomes prayer.