Introduction

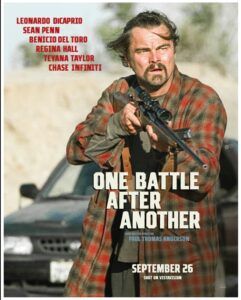

Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another (2025) is not only a political action film and a familial drama, but also a rich site for exploring how race and power intersect in contemporary America. Through its characters, narrative structure, and symbolic elements, the film interrogates white supremacy, fetishization, racialized authority, and resistance. This essay argues that Anderson uses the relationship between characters—especially Perfidia Beverly Hills and Col. Steven J. Lockjaw—as well as institutional forces like militias, the “Christmas Adventurers Club,” and border control operations to dramatize that power is often racialized, gendered, and both personal and systemic.

Race, Identity, and the Revolutionary “Other”

-

Perfidia and Racial Agency

Perfidia Beverly Hills (Teyana Taylor) is central to the film’s interrogation of race. As a Black revolutionary leading militant actions (e.g. assaulting a migrant detention center), she embodies resistance but also challenges normative expectations of Black womanhood. Her physicality, sexual agency, and confrontational stance with white authority figures disrupt power norms. The film allows her to be more than a supporting revolutionary; she is subject, agent, and a figure whose every act of resistance carries racial weight.

Lockjaw’s Fetishization and White Supremacy

Colonel Steven J. Lockjaw (Sean Penn) represents the oppressive, racialized state and the ways in which white supremacist power can both dominate and desire. Critics note that Lockjaw is haunted by his humiliation by Perfidia, and his subsequent obsession mixes racist control with sexual fascination. That dynamic—power through the gaze, sexual desire, threat of violence—is racialized and gendered. The fact that a white supremacist sees Perfidia not merely as an opponent but as an object for domination reveals how racial power often intersects with sexual control.

Institutional and Structural Power

Beyond individual characters, the film depicts institutionalized power: ICE-like detention centers, anti-immigrant forces, militarized law enforcement, and explicitly racist elite clubs. The “Christmas Adventurers Club,” a white supremacist fraternity-like group, illustrates how racial power is anchored in social, political, and cultural institutions that claim moral and ideological legitimacy. Their desire for “racial purification” is not hidden—it’s part of their structural position of privilege.

The Dynamics of Power: Conflict, Resistance, and Ambiguity

-

Conflict as Performance and Symbol

Many of the interactions between revolutionaries and authorities in the film are staged with spectacle: raids, bombings, daring escapes. These are not just plot points but symbolic performances of racial conflict. The opening raid on the detention center, for example, is both a literal rescue mission and a symbolic assertion that racialized power structures (immigration detention, the border, state control over “other” bodies) can be contested.

Resistance, Compromise, and Moral Complexity

The film does not present resistance as unproblematic. Characters like Perfidia make hard choices (betrayal, putting revolution over family) that raise questions about the costs of resisting power. Bob (formerly “Ghetto Pat”) must live in hiding, shift identities, and deal with the fallout of both his actions and his inactions. The generational conflict (Bob vs. his daughter Willa) also shows how power dynamics shift inside families and how racial identity gets transmitted under strain.

Ambiguity, Seduction, and the Personal Effects of Power

Anderson mixes satire, action, and drama to show that power is seldom monolithic. Lockjaw is clearly villainous, but he isn’t a caricature without dimension—his obsession with Perfidia has emotional and psychological textures. Perfidia likewise is heroic, but her heroism includes flaws, internal conflict, and difficult moral trade-offs. This complexity helps the film avoid a simple “good vs evil” framing; power is embedded in relationships, desire, fear, and betrayal.

Visual, Cinematic, and Symbolic Representations

-

Imagery & Cinematography

The visual contrast in the film between safe/hiding spaces and spectacle (raids, action scenes, the opulence of elite white supremacist settings) makes the power dynamics visible. Anderson and cinematographer Michael Bauman juxtapose intimate father-daughter moments with sweeping landscapes, high-stakes chases, and militarized settings. These shifts in scale mirror shifts in power.

Costume, Setting, and Rhetoric

Costuming and setting reinforce racial and power codes. For example, the “Christmas Adventurers Club” is dressed like old-money elite whites; uniforms, luxury, and ritual signifiers mark their power. Perfidia at times subverts such codes (her appearance, her bold actions), creating tension. The border detention scenes, immigrant networks, underground tunnels—these settings aren’t just backdrops but sites where systemic power is exercised, resisted, and mediated.

Implications: What the Film Suggests About Race, Power, and Redemption

-

Historical Resonance & Contemporary Parallels

Though loosely based on Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland, the film situates its story firmly in contemporary concerns: immigration, detention centers, white supremacist elites, polarized politics. Anderson uses race and power not just for period drama but to reflect how these structures persist.

Power as Relationship

The film suggests that power is relational: between oppressor and oppressed, between loved ones, between parent and child. Characters who appear powerless still exert agency (Willa, Perfidia, Sergio), while those with power (Lockjaw, elite club members) are often insecure, obsessive, haunted. Power is therefore not total; it is unstable, contested. Redemption or resistance requires acknowledging these relationships.

Limits of Power and the Possibility of Change

By the end, the film doesn’t offer a naive “everything is fixed” resolution. But it shows that individual and collective action matter. Willa’s growth, Bob’s attempt to reconcile his past, the exposure of institutions—these suggest that power structures, even deeply embedded ones, can be challenged. The trade-offs and costs are real; complete victory is elusive. The film seems to suggest that “one battle after another” is both a burden and a necessity.

Conclusion

One Battle After Another intensifies the conversation around race and power by dramatizing not just overt conflict but the subtle, intimate, and often ambiguous ways they operate. Through its characters like Perfidia, Lockjaw, Bob, and Willa; through its settings and imagery; and through its narratives of resistance, betrayal, and paternal love, the film shows that power is never simply possessed—it is exercised, coveted, resisted, and sometimes subverted. Anderson’s film forces us to see how race is embedded in power—both in institutions and in deeply personal spaces—and how redemption and identity depend on acknowledging, confronting, and moving through that reality.

Sources

-

The Ringer — “‘One Battle After Another’ Is Paul Thomas Anderson at His Best” The Ringer

-

The Washington Post — review “’One Battle After Another’…border detainment facility” The Washington Post

-

Roger Ebert — review of One Battle After Another Roger Ebert

-

Pitchfork — “One Battle After Another Review: A Nerve-Racking Masterpiece” Pitchfork

-

Time — “The Wild Political Story Behind ‘One Battle After Another’” TIME

-

Variety — changes from Vineland to One Battle After Another Variety

-

The Guardian — politics and themes in One Battle After Another The Guardian

- https://www.lemonde.fr/en/culture/article/2025/09/26/paul-thomas-anderson-s-epic-race-across-a-divided-america-in-one-battle-after-another_6745748_30.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com