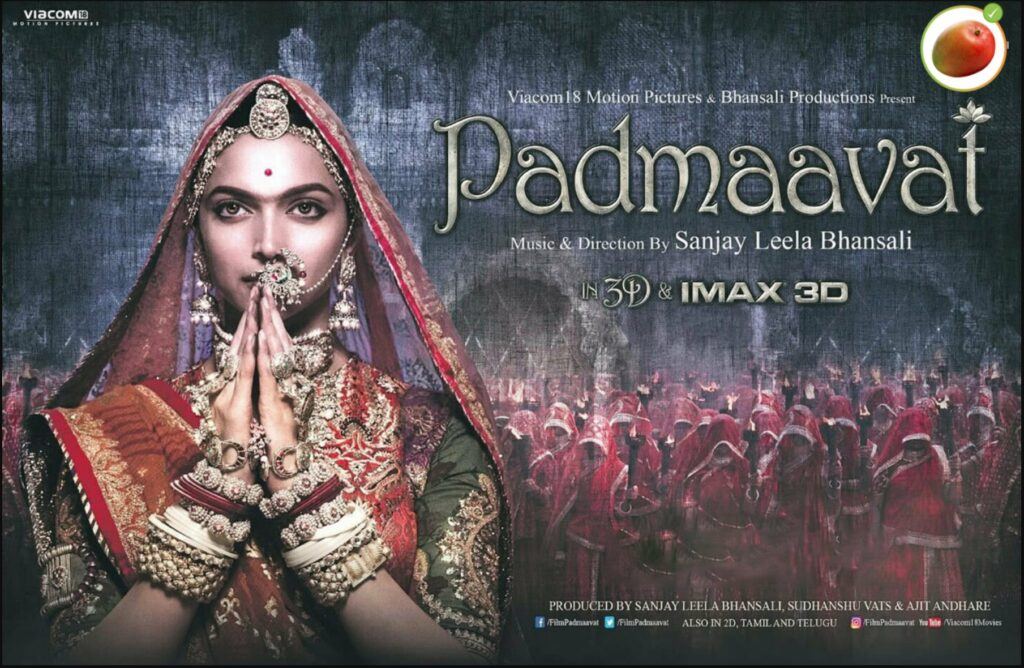

There are films that tell stories, and there are films that dream them. Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Padmaavat belongs to the second kind — a fever dream rendered in silk and smoke. It glows like a medieval miniature painting, but behind that beauty lurks a terrible gravity: the pull of power, the intoxication of desire, and the impossible ideal of purity in a world obsessed with possession.

To call Padmaavat merely a period epic is to undersell it. It is mythology masquerading as history, opera disguised as tragedy. It’s not about who ruled or who conquered, but about what happens when a woman’s image becomes the currency of kingdoms.

The Politics of Beauty

At the heart of Padmaavat lies a paradox: beauty as liberation, and beauty as curse. Queen Padmavati (Deepika Padukone) is not just beautiful; she is mythically beautiful — the kind whose reflection can start wars. Her radiance becomes legend, and legend becomes weapon.

When Alauddin Khilji (Ranveer Singh) hears of her, his desire turns into obsession. He doesn’t want her — he wants the idea of her. That’s the true colonial impulse of desire: to possess what cannot be possessed.

Bhansali paints this dynamic not as a love triangle, but as an allegory for domination. Khilji’s lust is imperial — he wants to own the unownable, to define the undefinable. Padmavati becomes the symbol of a land, a culture, a selfhood that refuses to yield. Her beauty, therefore, is not vanity — it’s defiance. It is the reminder that what glitters in the light cannot be controlled by those who live in shadow.

The Gaze and the Mirror

In Padmaavat, every gaze is an act of violence. Khilji gazes to conquer; Padmavati gazes to understand. And Bhansali, the director, gazes to mythologize.

When Khilji finally sees Padmavati’s reflection — that brief, forbidden glimpse through a mirror — it becomes the film’s moral axis. The mirror becomes a battlefield. The reflection, a duel between power and purity. She remains untouchable, and that untouchability drives him mad.

The mirror scene reveals the true heart of Padmaavat: beauty has power only when it refuses to perform. Khilji’s rage is the rage of the colonial and the patriarch alike — the fury of being denied access to the sacred.

In Bhansali’s universe, mirrors are never just mirrors. They’re metaphysical spaces — portals of meaning where identity and illusion blur. When Padmavati’s face glows in the mirror’s glass, it’s not vanity; it’s resistance. The woman being looked at is also looking back.

Desire as Empire

Alauddin Khilji is not simply a villain; he is appetite incarnate. His palace drips with meat and gold, his laughter echoes in rooms heavy with conquest. He is the embodiment of imperial hunger — not just for land, but for narrative control.

His pursuit of Padmavati is the pursuit of sovereignty over imagination. In his world, to desire is to dominate. And therein lies the tragedy: empire always confuses possession with love.

Ratan Singh (Shahid Kapoor), by contrast, represents order — decency, restraint, idealism. He loves Padmavati without consuming her. But his nobility is also his flaw; he plays by moral rules in an immoral game.

Their triangle — Ratan’s honor, Padmavati’s intellect, Khilji’s chaos — becomes a study in how different forms of power collide. The imperial, the moral, and the mythic orbit each other like planets destined to crash.

The Fire of Jauhar

No image in modern Indian cinema has been more haunting — or more contested — than Padmavati walking into the flames. It is both martyrdom and defiance, victory and void.

Bhansali stages it with terrifying beauty: a procession of women cloaked in red, walking into the sun, their faces serene as hymns. It’s a sequence that resists easy morality. On one hand, it celebrates choice — the refusal to be conquered. On the other, it mourns the terrible price of purity.

The fire in Padmaavat is not passive; it’s sentient. It devours with elegance, purifies with rage. The act of jauhar is framed not as surrender, but as reclamation — the only form of freedom left in a world where every other has been stripped away.

The flames become the film’s last mirror. The empire sees its own reflection and burns.

Myth and Masculinity

Bhansali’s cinema has always been about extremes — emotions painted in baroque intensity, morality lit like stained glass. But Padmaavat uses excess as philosophy. It asks: what happens when masculinity is defined by conquest?

Khilji’s masculinity is devouring; Ratan’s, devotional. Both fail in their own ways. Only Padmavati transcends. She becomes myth not because she seeks it, but because the world leaves her no other role.

She embodies a form of Indian femininity that is both soft and invincible — one that fights not with swords, but with the refusal to yield. Her final act is both political and cosmic. It tells the empire, and the gaze, and history itself: you cannot have me.

Light, Color, and the Language of the Sacred

Every Bhansali frame feels carved from devotion. The reds in Padmaavat are not colors — they are liturgies. The golds shimmer like hymns. The film’s palette tells the story long before the dialogue does.

The British colonial painter once sought to drain Indian color into sepia — to rationalize its wildness. Bhansali restores that color to sacred excess. His vision of India is unapologetically ornamental, because ornament itself becomes resistance.

In Padmaavat, color is theology. Red for love, yes — but also for sacrifice. Gold for beauty, yes — but also for power. Every hue becomes argument.

The Empire Within

Perhaps the most unsettling truth Padmaavat suggests is that colonization is not always external. Sometimes, it hides in the mind — in the belief that virtue is fragility, that purity must self-destruct to stay intact.

Khilji represents the outer empire — the invader, the other. But his hunger also mirrors something internal: India’s own obsession with sanctity and self-sacrifice. The film’s tragedy is not just about conquest; it’s about how power colonizes imagination.

Padmavati’s death ends a war, but it also seals a myth. A woman becomes eternal — and therefore, unreachable.

Conclusion: The Afterimage

When the flames die down, what remains is silence — not of defeat, but of awe. Padmaavat is a film about beauty weaponized and worshipped, about how stories survive by turning pain into ritual.

Bhansali’s India is not a map; it’s a hallucination — one where devotion and desire are inseparable, and where freedom often comes disguised as fire.

In the end, Padmavati does not win or lose. She transcends. Her fire becomes memory, her reflection legend, her name — invocation.

Because in Bhansali’s universe, beauty is never passive.

It burns.