When Thugs of Hindostan opens, the sea is not blue — it’s gold, brown, and furious. Waves crash like drums announcing an empire’s arrival. Ships glide in with crosses and cannons, bringing with them not just trade, but a philosophy of control.

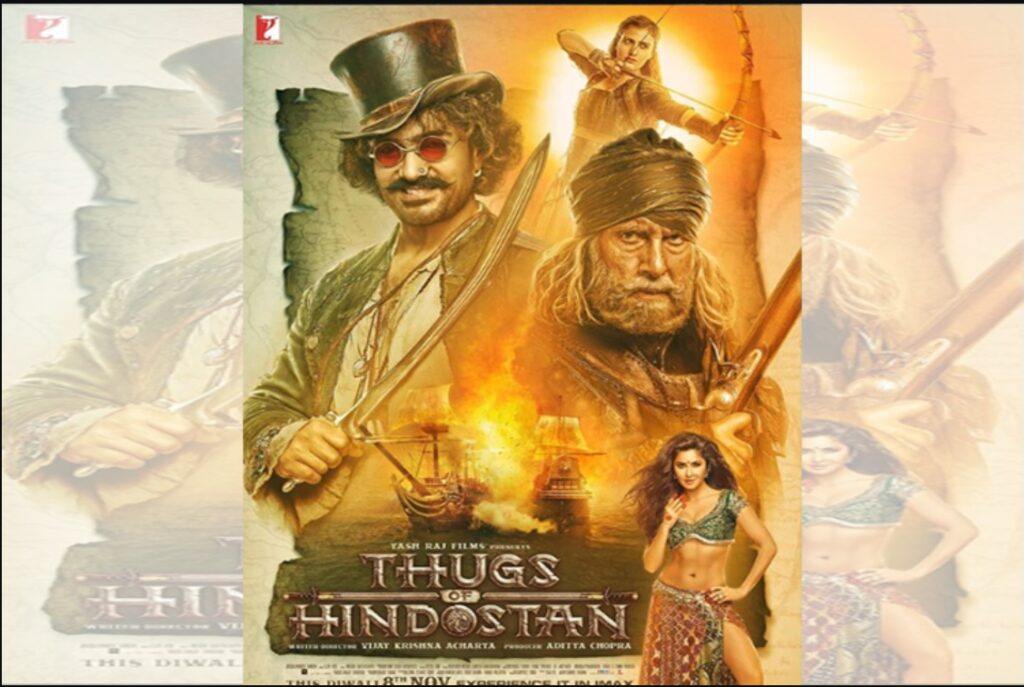

This is the empire’s true genius: it arrives smiling. It builds schools, writes laws, and hands out manners — all while emptying the land of its dignity. In Vijay Krishna Acharya’s Thugs of Hindostan, that story is told not through history books but through performance — masks, music, betrayal, and the shimmer of spectacle. Beneath its crowded canvas of swords and sails lies the quiet heartbeat of a people learning to breathe again.

The Empire’s Theater

Colonization, the film suggests, is a kind of theater — elaborate, rehearsed, cruelly aesthetic. The British command not just through guns, but through presentation. Their uniforms gleam. Their accents drip with authority. Every gesture declares, We belong to the future; you belong to the past.

The Indians, meanwhile, are reduced to spectators on their own stage. They are told their gods are quaint, their stories irrelevant, their colors too loud. They are tolerated as curiosities — as long as they stay in costume.

But Acharya’s camera does not bow to that hierarchy. It lingers on Indian faces, lit by fire, not shame. It watches their sweat and their laughter with reverence. It allows the colonized body to occupy the frame as something whole, not fragmented — not an ornament, but an origin.

In every wide shot of dusty plains or crowded markets, the film insists: the land remembers. No empire can own what was born of monsoon and myth.

The Language of Racism

The racism in Thugs of Hindostan is not loud. It does not scream in slurs; it whispers in bureaucracy. The British officers never call the Indians inferior — they demonstrate it in a hundred polite gestures. The way they dismiss a question. The way they rename a city. The way they treat silence as obedience.

Colonial racism thrives not on hatred, but on condescension. It claims moral superiority — a righteousness that believes domination is charity. When the British character Clive (modeled on the East India Company’s archetype) speaks of “civilizing,” his words drip with the poison of certainty. His racism is so confident it mistakes itself for kindness.

Against that, the Indians fight with irony, not rage. Firangi (Aamir Khan) mocks the empire’s rituals by imitating them. He is a trickster — fluent in hypocrisy, slippery in allegiance. His name means “foreigner,” but his soul belongs to India’s fractured heart. He is what empire creates — an Indian who survives by mimicry, who learns to weaponize the colonizer’s mask.

In his deceit, there’s genius: he turns imitation into rebellion.

Faith, Betrayal, and the Currency of Survival

In the colonial order, loyalty is its own form of slavery. The empire rewards obedience with humiliation. Firangi’s journey — from opportunist to insurgent — mirrors the moral awakening of a nation that has mistaken patience for virtue.

He begins as a jester in the court of power, laughing too loud to avoid being crushed. But as the British grow crueler, his laughter curdles into rebellion. His transformation is not about heroism — it’s about the unbearable weight of complicity.

Colonization makes cowards of dreamers; racism teaches them to doubt their worth. Firangi’s redemption, then, is not just political — it is existential. To betray the empire is to reclaim the self.

Women, Resistance, and the Sacred

In the empire’s story, women are always decoration. But Thugs of Hindostan rewrites that script. Zafira (Fatima Sana Shaikh) — warrior, survivor, heir to a slaughtered kingdom — carries rebellion in her silence. Her bow is her voice; every arrow she fires speaks for a lineage denied language.

Her resistance is deeply Indian — not in costume or rhetoric, but in its fusion of faith and fury. She fights not for conquest, but for memory. Each gesture is an act of mourning and defiance.

The British call it savagery; she calls it justice.

Spectacle and Subversion

Critics called Thugs of Hindostan excessive — too loud, too grand, too indulgent. But perhaps that excess is the point. Empire itself was a spectacle, a theater of control. Why shouldn’t rebellion answer with its own pageantry?

The songs, the explosions, the flamboyant humor — all of it masks something sacred: the refusal to be invisible. Indian cinema has always understood that beauty can be political. To dance in chains is still to declare, I am alive.

And when Firangi sails into the sunset at the end, his smirk isn’t mere triumph — it’s a promise. The Indian trickster, once mocked for his duplicity, has outlived the empire’s certainty.

The Color of Freedom

In this film, the colors tell the truth the dialogue cannot. The British world is pale, metallic, almost sterile. The Indian world burns — in saffron, crimson, and smoke. The visual contrast is racial and spiritual: order versus vitality, coldness versus chaos.

Racism in Thugs of Hindostan is obsessed with tidiness — the empire demands everything be categorized. The Indian world resists categorization by existing as excess — too vivid, too emotional, too alive.

When the rebels rise, they do so not just as soldiers, but as artists. Their freedom is aesthetic. Their victory is a restoration of color.

Freedom as Invention

What the film ultimately argues is that freedom is not found — it is imagined. The empire claimed to bring reason and progress, but what it really brought was repetition. The Indian rebels, by contrast, bring improvisation — the ability to dance through disaster, to laugh in loss, to outwit the narrative of inferiority.

When the British ships finally burn, the smoke curls upward like incense — not destruction, but purification. It is the empire’s own spectacle turned against itself.

The Sea Remembers

The film ends where it began — at sea. The waves glow with firelight, the horizon endless. The Indian revolution in Thugs of Hindostan is not complete; it never can be. Empire does not vanish overnight — it lingers in language, in memory, in the mirror.

But the film insists on one truth: the sea remembers who sailed it first. It remembers Indian traders, Indian gods, Indian songs — long before the white sails arrived.

And in that remembering lies freedom. Not vengeance, not victory — but memory reclaimed, identity reinhabited.

Epilogue: The Trickster’s Gift

In the end, Firangi — thief, liar, survivor — stands as India’s mirror. He embodies a nation that learned to wear masks until it could make its own. Colonization taught Indians how to perform; independence will teach them how to improvise.

And perhaps that’s the quiet genius of Thugs of Hindostan: it understands that resistance need not always be pure. Sometimes, it’s clever. Sometimes, it cheats. Sometimes, it smiles.

But always — always — it survives.