Ronan Day-Lewis’s Anemone (2025) is a stark, meditative exploration of guilt, faith, and redemption. Centered on two estranged brothers — Ray, played by Daniel Day-Lewis in his long-awaited return to acting, and Jem, portrayed by Sean Bean — the film unfolds as a quiet confrontation between belief and despair, sin and forgiveness. It is not merely a family drama, but a philosophical inquiry into the human need for absolution and the elusive presence of God in a world stripped of divine order. Through its spare dialogue, severe natural imagery, and restrained performances, Anemone reimagines the sacred as something fragile, painful, and deeply human.

At its core, Anemone examines the silence of God. Ray lives alone in the wilderness, seeking isolation as a form of penance. The forest around him is both sanctuary and punishment, a place where he confronts memories of childhood abuse and acts of violence committed in adulthood. In traditional theology, silence may be a sign of divine mystery — God’s presence hidden within absence. Yet in Anemone, silence feels closer to exile. Ray’s separation from society, and from faith itself, becomes the film’s most profound statement on the collapse of moral order. His brother Jem, by contrast, represents the vestige of structured religion. He clings to ritual and community, attending church and invoking scripture, yet his belief offers him little peace. Through these contrasts, Day-Lewis suggests that faith can be both refuge and burden — a framework that comforts some and condemns others. The film’s sound design, filled with long pauses and natural ambience, makes God’s absence almost tangible, pressing upon the characters like the air itself.

If God is distant, Anemone asks whether absolution can exist without divine mediation. Traditionally, forgiveness in Christian theology requires confession, ritual, and an intermediary — the priest, the church, the cross. Day-Lewis strips away those structures. When Ray finally recounts the violence he has endured and inflicted, the confession occurs not in a sacred space but in a cold wooden cabin, with only his brother as witness. Jem becomes an accidental confessor, standing in for the absent God. Ray’s admission is raw, unsanctioned, and painful, and when Jem offers comfort, Ray refuses it: “I don’t need your absolution.” The line captures the paradox of guilt — that the very act of denying forgiveness reveals an unspoken longing for it. In Anemone, confession is no longer a transaction but an act of vulnerability. Absolution, if it exists, must arise from human understanding, not divine decree.

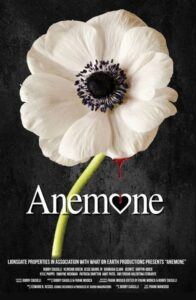

The film’s title deepens its meditation on the sacred. The anemone flower, delicate and fleeting, has long been associated with themes of death and resurrection. In Greek myth, it springs from the blood of Adonis, symbolizing both loss and renewal. In Christian iconography, it is linked to the Passion — the wounds of Christ and the hope of resurrection. Day-Lewis uses the flower as a visual motif throughout the film: small patches of red and white petals appear in the harsh grey landscape, reminders of beauty persisting amid decay. The natural world becomes a kind of inverted cathedral — the wind and light replacing organ music and stained glass. For Ray, tending to a small garden of wild anemones becomes his only ritual, a silent prayer performed without words. Nature, in its quiet endurance, replaces God as the source of meaning and mercy.

Yet Anemone ultimately resists offering closure. The brothers’ reconciliation is partial, hesitant, perhaps even illusory. There is no climactic act of redemption, no divine sign of grace. Instead, the film ends with the two men sitting side by side in silence, the camera lingering on their faces as light shifts through the trees. In this stillness lies the film’s most radical claim: that forgiveness may not erase sin but simply allow life to continue beside it. Absolution, in Anemone, is not a cleansing but a coexistence — the acceptance of brokenness as part of being human. The film implies that true absolution cannot be granted by others or by God; it can only emerge from one’s willingness to remain open, to be seen, and to endure.

Through its austere beauty and emotional restraint, Anemone transforms traditional religious imagery into psychological truth. God is no longer the arbiter of moral law but a symbol for the human yearning to be forgiven. Absolution becomes not a ritualized act but a slow, painful awakening to empathy. In the end, what Anemone proposes is both devastating and hopeful: that divinity survives not in the heavens but in the fragile connections between flawed people. The sacred, it suggests, is not something we seek beyond ourselves — it is the courage to forgive, and to keep living in the silence that follows.